We’re in an age of amazing reprint volumes resurrecting all genres of comics history—but this is the last week in October, so it’s time to carve out some space for two of the latest Pre-Code horror comicbook collections!

We’re in an age of amazing reprint volumes resurrecting all genres of comics history—but this is the last week in October, so it’s time to carve out some space for two of the latest Pre-Code horror comicbook collections!

And who better to begin with than…

Frankenstein!!!

_______________________________________

Comics archivist/scholar/historian/collector/editor Craig Yoe has been behind some of the most invigorating of the new collections of ancient work, including George Herriman’s Krazy + Ignatz “Tiger Tea,” The Golden Collection of Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Komics, Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails, Dan DeCarlo’s Jetta, The Art of Ditko, and two recently reviewed here on the Schulz Library Blog,

True to his love of vintage comics creators who embrace both the bizarre and the bawdy, Yoe‘s 2010 Halloween seasonal release this month offers a definitive collection of the one Pre-Code horror comic that schizophrenically shifted between the hilarious and the horrific: Dick Briefer’s Frankenstein!

As Yoe details in this new volume’s excellent (and heavily illustrated) introduction, Briefer (1915-1980) attended classes in the late 1930s under Robert Brackman at New York City’s famed Art Students League before starting his comicbook career laboring in the Will Eisner/Jerry Iger sweatshop. Among Briefer’s earliest creations were an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (for Jumbo Comics; Yoe offers a reproduction of the first installment’s splash page), space heroes Rex Dexter (for Mystery Men Comics) and Crash Parker (Planet Comics), “The Pirate Prince” (for Silver Streak and Daredevil), Yankee Longago (Boy Comics), Biff Bannon (Speed Comics), and superheroes like Dynamo, Real American #1 (yep, that was his name!), Target and the Targeteers, and the Human Top, among others.

Like many Golden Age creators, Briefer was incredibly prolific (at the meager page rates available, the only way to keep a roof overhead and food on the table was to grind out pages as quickly as possible) and worked under a variety of nom de plumes as well as his own name. Among the pseudonymous strips some comics scholars attribute to Briefer were the adventures of Communist hero Pinky Rankin for The Daily Worker (a stint that may or may not have been Briefer’s work, and may or may not have landed Briefer on McCarthy era blacklists).

Briefer‘s claim to fame, however, was and remains his innovative horror comic series “The New Adventures of Frankenstein,” which debuted in Prize Comics #7 (cover dated December 1940, meaning it hit the racks in the fall of that year). Briefer did everything—script, lettering, pencils, inks—on this new feature for the Crestwood Publishing Company (aka Feature Publication and Prize Comics), which may have been the first contemporary spin on Mary Shelley‘s venerable 1818 source novel.

The catalyst for Briefer’s resurrection of Shelley’s immortal monster was arguably the 1939 Universal Pictures re-release of the two feature films that launched their beloved 1930s horror cycle, Tod Browning‘s Dracula (1930) and James Whale‘s Frankenstein (1931). Universal had abandoned the genre by the mid-1930s, due in part to the loss of the entire British (and British colonies) market, where horror films were proving less and less marketable since the British censors had instituted the dreaded ‘H’ certificate. By the end of the decade, Universal’s fortunes had dwindled, and the surprise success of a regional “midnight movie” showing of the Dracula/Frankenstein double-feature prompted Universal to roll the double-bill out nationally and to rekindle their horror line with the production of an all-new Frankenstein entry, Rowland V. Lee‘s Son of Frankenstein (1939). It was a smash hit, saving Universal’s fortunes and kicking off a whole new horror movie cycle that lasted into the mid-1940s (ending with Universal’s parody Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, 1948).

The catalyst for Briefer’s resurrection of Shelley’s immortal monster was arguably the 1939 Universal Pictures re-release of the two feature films that launched their beloved 1930s horror cycle, Tod Browning‘s Dracula (1930) and James Whale‘s Frankenstein (1931). Universal had abandoned the genre by the mid-1930s, due in part to the loss of the entire British (and British colonies) market, where horror films were proving less and less marketable since the British censors had instituted the dreaded ‘H’ certificate. By the end of the decade, Universal’s fortunes had dwindled, and the surprise success of a regional “midnight movie” showing of the Dracula/Frankenstein double-feature prompted Universal to roll the double-bill out nationally and to rekindle their horror line with the production of an all-new Frankenstein entry, Rowland V. Lee‘s Son of Frankenstein (1939). It was a smash hit, saving Universal’s fortunes and kicking off a whole new horror movie cycle that lasted into the mid-1940s (ending with Universal’s parody Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, 1948).

Whether Briefer was directly or indirectly inspired to launch his own Frankenstein comic series by the revival of the Universal monster movie series and/or the Movie Comics adaptation, who can say? The fact is, those were the most direct precursors to Briefer’s series, which took the public’s conflation of the creator (Frankenstein) and his monster (Frankenstein’s monster) as a given—the monster was Frankenstein in name—and ran with it. Briefer took the public’s identification of the monster with its creator one step further, signing the original installments “by Frank N. Stein.”

“I had a hard time convincing the publisher that [Shelley’s Frankenstein] was in public domain,” Briefer told interviewer Howard Leroy Davis, but it was, and Briefer thrust the monster into a new life with Prize Comics #7’s revisionist take on the monster’s birth. Beginning as an apparent Gothic, Briefer depicted Dr. Victor Frankenstein’s construction of the monster from “the dead bodies of scores of men” in an efficient single page; by page three, the monster was on the loose, and by page five (“one fine day at the zoo…”), 1939 readers were begin to fathom that this resurrection had somehow taken place in then-modern-day America! Briefer had his monster escaping the zoo on an elephant, terrorizing the Big Apple, climbing the Statue of Liberty and sparing the life of his creator as an act of revenge:

“I spared you to live—to live in misery also—to watch and see the suffering and grief that I, your creation, will cause the human race!”

And so it began! Briefer’s original series was indeed a straight horror-adventure comic, the first of its kind in American comics history (seven to eight years before the first horror anthology comics surfaced with Avon’s 1947 one-shot Eerie #1 and American Comic Group’s long-lasting periodical Adventures Into the Unknown, which debuted in 1948). Craig Yoe offers the first three installments of Briefer’s initial series (pp. 21-44 of the collection)—which includes the monster’s one-on-one urban battle with a crocodile man—whetting one’s appetite for a complete reprint collection of the entire Briefer original series.

Briefer’s revamp of the monster’s design emulated some aspects of Universal makeup genius Jack Pierce‘s original ‘look’ for actor Boris Karloff‘s movie incarnation of the monster: the squared-off skull, the ragged sutures across the forehead, the cadaverous pallor and sunken cheeks. But Briefer skirted any legal claims Universal might have made by traumatically rearranging the monster’s facial features, squashing the flattened nose directly beneath the knobby brows and between the outsized eyes, and dispensing with the electrode (“bolts”) protruding from the neck. Briefer’s monster was indeed hideous, and Briefer cranked out a tsunami of terror tales featuring the creature through to the April 1945 issue of Prize Comics #52 and the launch of Frankenstein in his own title that same year.

Briefer’s revamp of the monster’s design emulated some aspects of Universal makeup genius Jack Pierce‘s original ‘look’ for actor Boris Karloff‘s movie incarnation of the monster: the squared-off skull, the ragged sutures across the forehead, the cadaverous pallor and sunken cheeks. But Briefer skirted any legal claims Universal might have made by traumatically rearranging the monster’s facial features, squashing the flattened nose directly beneath the knobby brows and between the outsized eyes, and dispensing with the electrode (“bolts”) protruding from the neck. Briefer’s monster was indeed hideous, and Briefer cranked out a tsunami of terror tales featuring the creature through to the April 1945 issue of Prize Comics #52 and the launch of Frankenstein in his own title that same year.

Prize Comics #53’s “Frankenstein and the Beanstalk” was the last of the fantasy-horror Briefer Frankensteins; with a new original story in Frankenstein #1 (“Frankenstein’s Creation,” reprinted complete in the Yoe collection, pp. 45-59) and Prize Comics #53’s “Pour Out Your Heart,” Briefer redirected his ongoing feature, transforming it into an adsurdist kid-friendly horror-comedy comic!

By this point, Briefer’s distinctively fluid brushwork had become absolutely breezy and more expressive than ever, and the complete change in tempo, temper, and tone suited his brushline. It was a new lease on life for Briefer and his beloved monster, whose nose slid progressively further up into his browline within the pages of Frankenstein #1 alone (as demonstrated in this collection’s generous reprint of no less than three stories from that historic first issue)!

By this point, Briefer’s distinctively fluid brushwork had become absolutely breezy and more expressive than ever, and the complete change in tempo, temper, and tone suited his brushline. It was a new lease on life for Briefer and his beloved monster, whose nose slid progressively further up into his browline within the pages of Frankenstein #1 alone (as demonstrated in this collection’s generous reprint of no less than three stories from that historic first issue)!

By 1947, Briefer was writing and drawing Frankenstein (now labeled “The Merry Monster”) for Prize Comics and for the character’s solo series (!). Editor Yoe offers two other Briefer comedic Frankenstein stories from this period, “Blooperman” (from Frankenstein #8, July-August 1947), included herein due to its pointed satire on the most popular four-color superhero of them all (and in case you’ve any doubt, Briefer’s satiric byline for the story, “by Seagull & Shoestring,” puts paid to that), and the beguiling Spirit parody “The Girl with the Bewitching Eyes” (from Frankenstein #15, September-October 1948). Well, I’d tag it as an Eisner parody, if only for its femme fatale, Zona, but the whole of Briefer’s approach to this one Frankenstein tale smacks of Eisner’s iconic 1940s body of work.

“Blooperman” (from Frankenstein #8, July-August 1947), included herein due to its pointed satire on the most popular four-color superhero of them all (and in case you’ve any doubt, Briefer’s satiric byline for the story, “by Seagull & Shoestring,” puts paid to that), and the beguiling Spirit parody “The Girl with the Bewitching Eyes” (from Frankenstein #15, September-October 1948). Well, I’d tag it as an Eisner parody, if only for its femme fatale, Zona, but the whole of Briefer’s approach to this one Frankenstein tale smacks of Eisner’s iconic 1940s body of work.

Briefer’s Frankenstein shifted gears again with the hardcore horror comics boom of the early 1950s, and Yoe offers a quartet of Frankenstein tales from Briefer’s return to horror amid the Pre-Code horror swamp. “Tomb of the Living Dead” (Frankenstein #20, August-September 1952), “Friendly Enemies!” (from #24, April-May 1953), “The She-Monster” (#28, January 1954) and “The Tree of Death” (#31, June-July 1954) are indeed representative of the swansong years of Briefer’s series. These aren’t the stories I’d have selected from this period in Briefer’s horror series (there are better ones, to my mind), but they’re interesting enough horror tales, sparked with inventive imagery and bits of business. Sadly, they lack the energy of Briefer’s earlier stories. Even the brushwork denotes his exhaustion with the 14-year-run, though ever the pro, Briefer doesn’t short-shrift the reader: the storytelling is crisp, clear, and the narratives provide enough twists to keep even the most jaded genre reader’s interest.

With Dick Briefer’s Frankenstein, archivist/editor/packager Craig Yoe continues to provide a service to the comics community. While this tome is as stylishly produced as all Yoe’s books—if anything, the cool die cutting of Frankenstein’s eyes lends this volume an appropriately children’s storybook flavor—Yoe has finally addressed the one complaint I have with too many of such compilations: Craig cites the original publication source, date, and year of publication on the first page of every story. Kudos, Craig, and here’s hoping this practice becomes standard operating procedure for all future collections.

Per usual, the color reproduction from the original comics retains the flavor of the Pre-Code four-color showcases, and the restoration work on the stories themselves is exquisite. While the Briefer Frankenstein comic stories have periodically been reprinted in the years since Briefer’s death—including reprints in Dr. Frankenstein’s House of 3D (1992), the Cracked monster magazines Cracked Monster Party (1988) and Monsters Attack! (1989-90), and a recent black-and-white paperback reprint volume entitled The Monster of Frankenstein (2006)—this current collection eclipses them all handily, while offering the most comprehensive overview of Briefer’s life, work, and the arc of the Frankenstein comics stories Briefer single-handedly created.

Yoe spices the stew with a generous helping of Briefer artwork from his other Frankenstein efforts, including his ill-fated comic strip proposal(s), stages of work (roughs, pencils, inks) preserved from Briefer’s process, and an eye-popping array of cover reconstructions Briefer painted and drew for fans later in his life.

Dick Briefer’s Frankenstein is the ideal Halloween/Christmas gift for any monster-lovin’ comics reader, and establishes a welcome new threshold for the entire Yoe/IDW line of reprint volumes. This is highly recommended reading, and as with all the Yoe collections, a grand entertainment from cover to cover.

– Stephen R. Bissette, Mountains of Madness, VT

It’s amazing what the ongoing romance between academia and comics continues to offer.

It’s amazing what the ongoing romance between academia and comics continues to offer. One major oversight in Hayton’s otherwise comprehensive overview of movie comics that predate the Charlton monster comics of the ’60s must be noted: Dick Briefer‘s long-running Frankenstein comics (debuting in Prize Comics in the 1940s and landing it own title — two series! — through to the mid-1950s), which certainly owed a debt to the ongoing popularity of the bastardized Mary Shelley Frankenstein cinematic adaptations, spin-offs and endless procession of family members (Bride of, Son of, etc.). Briefer’s Frankenstein began as a straightforward horror series, then metamorphosed into a bizarre humor comic, returning to action-horror during the Pre-Code horror comics boom of the early ’50s.

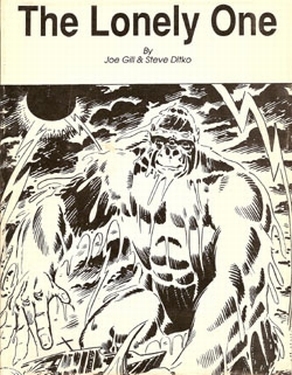

One major oversight in Hayton’s otherwise comprehensive overview of movie comics that predate the Charlton monster comics of the ’60s must be noted: Dick Briefer‘s long-running Frankenstein comics (debuting in Prize Comics in the 1940s and landing it own title — two series! — through to the mid-1950s), which certainly owed a debt to the ongoing popularity of the bastardized Mary Shelley Frankenstein cinematic adaptations, spin-offs and endless procession of family members (Bride of, Son of, etc.). Briefer’s Frankenstein began as a straightforward horror series, then metamorphosed into a bizarre humor comic, returning to action-horror during the Pre-Code horror comics boom of the early ’50s. Steve Ditko gleefully embraced the humor elements Gill introduced to the pages of Konga in particular, including a running gag in one issue (featured in The Lonely One; see below) involving a photograph of an attractive couple seen reacting to the action of the story. It’s a bit like Gyro Gearloose‘s lightbulb-headed robotic assistant in the Carl Barks Donald Duck /Uncle Scrooge comics (particularly the Gyro Gearloose comics themselves) — you can follow their comedic interaction like a little ‘mini-movie’ hidden inside the panels.

Steve Ditko gleefully embraced the humor elements Gill introduced to the pages of Konga in particular, including a running gag in one issue (featured in The Lonely One; see below) involving a photograph of an attractive couple seen reacting to the action of the story. It’s a bit like Gyro Gearloose‘s lightbulb-headed robotic assistant in the Carl Barks Donald Duck /Uncle Scrooge comics (particularly the Gyro Gearloose comics themselves) — you can follow their comedic interaction like a little ‘mini-movie’ hidden inside the panels. This kind of scholarly work is welcome, particularly for such previously-ignored (and indeed reviled) eddies in comics history. Growing up in Vermont, I was geographically close to Charlton’s base of operations (Connecticut), and Charlton titles had solid distribution even in the northern Green Mountain hinterlands. Hayton provides evidence of the wider popularity of the Charlton titles, and goes the extra mile to connect the Charlton 1960s monster movie comics with the contemporary industry standards, where their successors are popular fixtures of the comics market. Primary among those successors to Konga and Gorgo are the Dark Horse Aliens, Predator, and Aliens vs Predator, which indeed played a vital role in how the parent studio 20th Century Fox rebooted the film franchises themselves.

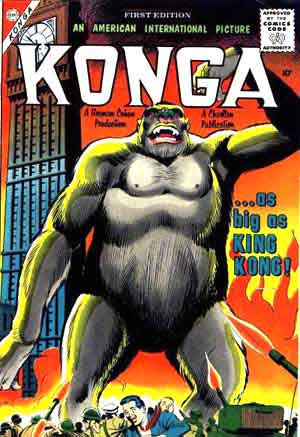

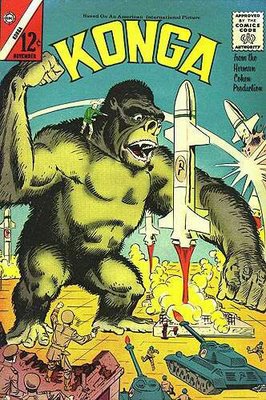

This kind of scholarly work is welcome, particularly for such previously-ignored (and indeed reviled) eddies in comics history. Growing up in Vermont, I was geographically close to Charlton’s base of operations (Connecticut), and Charlton titles had solid distribution even in the northern Green Mountain hinterlands. Hayton provides evidence of the wider popularity of the Charlton titles, and goes the extra mile to connect the Charlton 1960s monster movie comics with the contemporary industry standards, where their successors are popular fixtures of the comics market. Primary among those successors to Konga and Gorgo are the Dark Horse Aliens, Predator, and Aliens vs Predator, which indeed played a vital role in how the parent studio 20th Century Fox rebooted the film franchises themselves. [Above, right: Dick Giordano cover art for the original Charlton Konga #1, interior art by Steve Ditko; left: one of Ditko’s own Charlton Konga covers, finding Konga typically taking on a communist country’s ‘weapons of mass destruction’]

[Above, right: Dick Giordano cover art for the original Charlton Konga #1, interior art by Steve Ditko; left: one of Ditko’s own Charlton Konga covers, finding Konga typically taking on a communist country’s ‘weapons of mass destruction’] The Joe Gill/Steve Ditko Konga collection Robin Snyder published in 1989 was The Lonely One, and it’s an excellent introduction to this oddball genre.

The Joe Gill/Steve Ditko Konga collection Robin Snyder published in 1989 was The Lonely One, and it’s an excellent introduction to this oddball genre. [If you want to read more about this strange period in Charlton Comics history, check out the Myrant multi-chapter essay on Charlton, their paperback division Monarch Books, and the incredible story of

[If you want to read more about this strange period in Charlton Comics history, check out the Myrant multi-chapter essay on Charlton, their paperback division Monarch Books, and the incredible story of