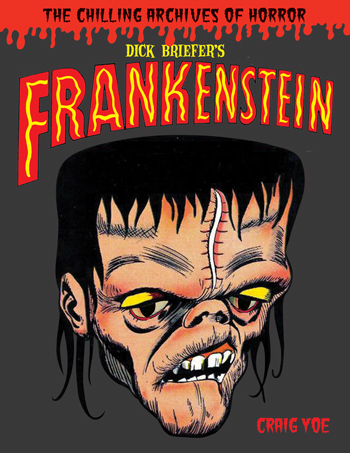

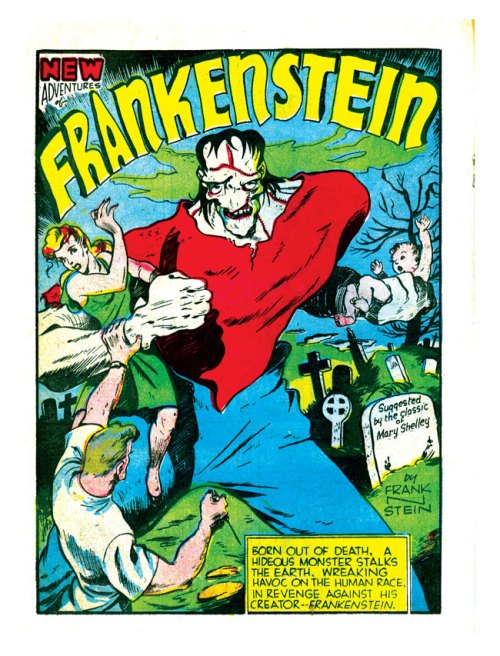

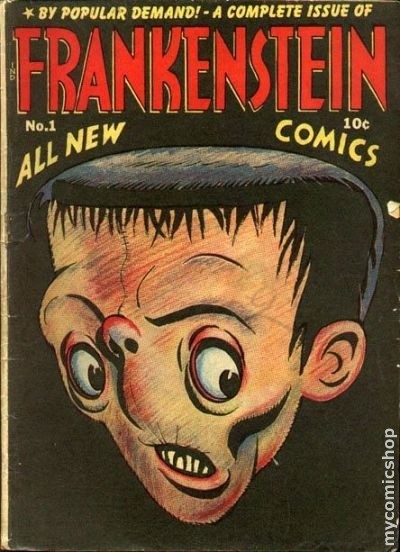

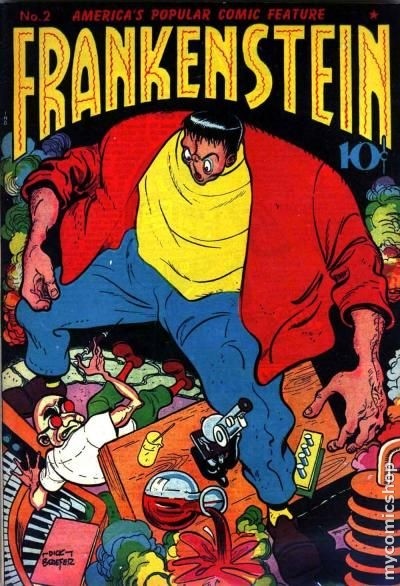

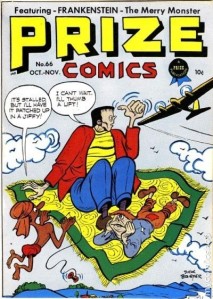

Three brand-new books on a long-despised and now fashionable genre—the oxymoronic genre of “horror comics”—have hit bookshops and library shelves over the past month, and CCS’s Schulz Library takes a look at all three this week. All three arrive on the heels of editor/packager/archivist Craig Yoe‘s handsome resurrection of Dick Briefer’s Frankenstein,

another slice of Pre-Code horror (and humor) comicbook history we reviewed here last month (in time for Halloween!).

It’s been a bountiful harvest for horror comics hounds this fall! Here’s a review of the first—and in many ways, the best—of the crop…

_________

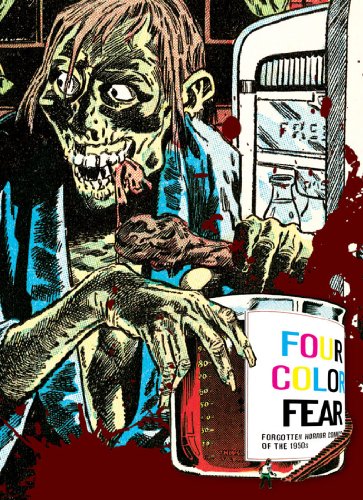

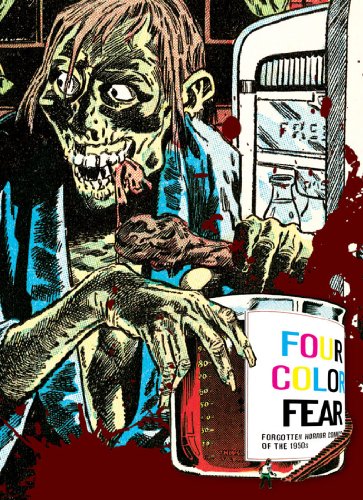

* Greg Sadowski‘s excellent Four Color Fears: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s (Fantagraphics Books) was the first of a quartet of books on horror comics to surface this fall, and for my money, it’s arguably the most invaluable of the bunch. Graced with an introduction and extensive additional material by vet horror comics scholar, archivist, collector, and expert John Benson, Four Color Fears offers over 300 pages of full-color complete stories lovingly selected from the non-EC Comics Pre-Code horror comics of the early 1950s.

For reasons clear to anyone with any access to the real Pre-Code horror comics, EC Comics has long dominated any and all books about the genre and the 1951-1954 boom years in particular. But there was plenty of other outstanding, outrageous, exciting, and just plain bizarre material published in that fleeting but jam-packed three-year period, and it’s high time we saw some of that work disintered and shared. While collectors have rescued and savored much of this work, it’s been nigh on impossible for non-collectors (including scholars and serious researchers) to access the non-EC Pre-Code horrors.

There are forty—count ’em, 40!—vintage horror comics stories showcased in this glorious collection. They are all reproduced from their original four-color printings, preserving the instrinsic flavor (and trash aesthetic) of the era and form, along with a handsome cover gallery insert (printed on slick paper) and abundant, informative, heavily illustrated notes on all the stories and what is known of their creators. This section of annotations also offers more delicious cover art, along with much previously unavailable information on the who, what, when, and how of the comics and creators themselves.

There are forty—count ’em, 40!—vintage horror comics stories showcased in this glorious collection. They are all reproduced from their original four-color printings, preserving the instrinsic flavor (and trash aesthetic) of the era and form, along with a handsome cover gallery insert (printed on slick paper) and abundant, informative, heavily illustrated notes on all the stories and what is known of their creators. This section of annotations also offers more delicious cover art, along with much previously unavailable information on the who, what, when, and how of the comics and creators themselves.

There are some real revelations here, and I can tell you that this hardcore horror comics scholar/collector/creator is eternally grateful for all that Sadowski and Benson have added herein to a richer knowledge of these unique comics and this grossly misrepresented and misunderstood period in comics history.

With an eye toward entertaining fully as well as curating, Sadowski’s greatest accomplishment here is making Four Color Fear such a fun and engaging read, cover-to-cover. Stories, and their order, have been chosen and orchestrated for optimum effect for casual reading, in the order presented. Let me tell you from hard experience (my years editing new horror comics stories in Taboo, 1988-93), that this is far easier said than done; in a genre grounded in provoking negative emotions for its primary effects (i.e., fear, dread, disgust, horror), it’s a real tightwire act to determine which stories belong where, and what effects are created by where an editor places a particular story, idea, or image. A misstep can either make or break a story, ending, or key moment, and careful orchestration of humor, horror, and variety is essential to making this sort of thing sing.

With an eye toward entertaining fully as well as curating, Sadowski’s greatest accomplishment here is making Four Color Fear such a fun and engaging read, cover-to-cover. Stories, and their order, have been chosen and orchestrated for optimum effect for casual reading, in the order presented. Let me tell you from hard experience (my years editing new horror comics stories in Taboo, 1988-93), that this is far easier said than done; in a genre grounded in provoking negative emotions for its primary effects (i.e., fear, dread, disgust, horror), it’s a real tightwire act to determine which stories belong where, and what effects are created by where an editor places a particular story, idea, or image. A misstep can either make or break a story, ending, or key moment, and careful orchestration of humor, horror, and variety is essential to making this sort of thing sing.

In this, Sadowsky brings far more care to his anthology than any of the original editors of these comics seemed to; the cumulative effect, at times, is intoxicating, and the ways in which both the individual art styles and the narrative content are woven into a satisfying tapestry are often witty, sly and insidious. There’s a lot of smart work, here, and as a result it’s a super read for everyone, whether you’ve never before sampled this era’s strange fruit or are (like me) a long-time fan and collector.

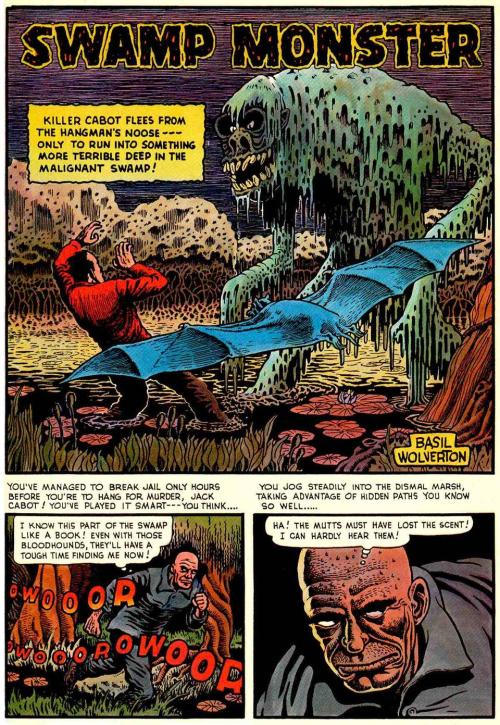

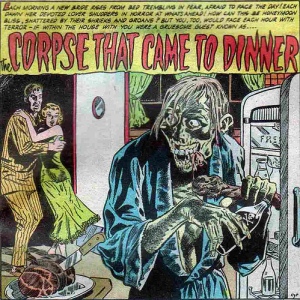

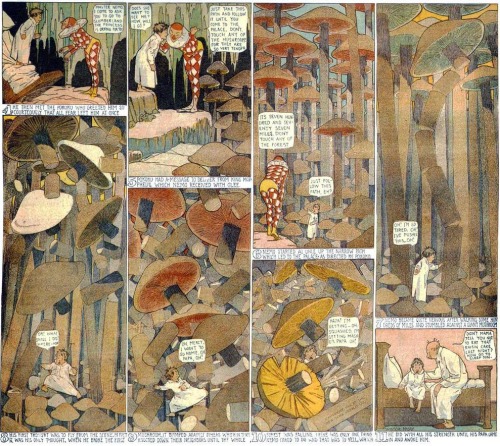

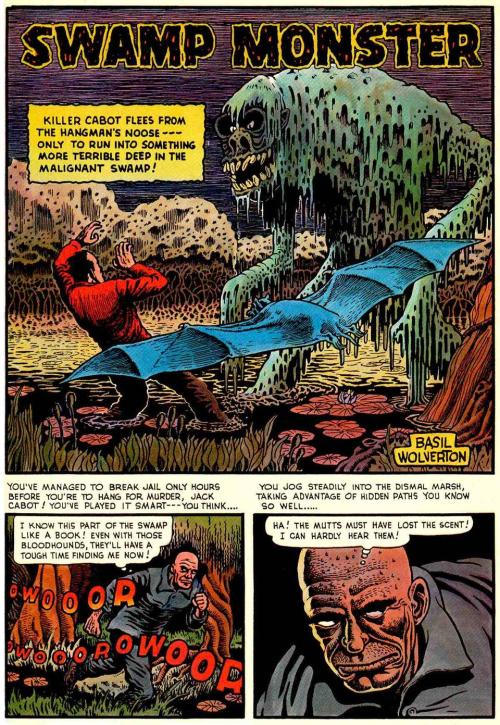

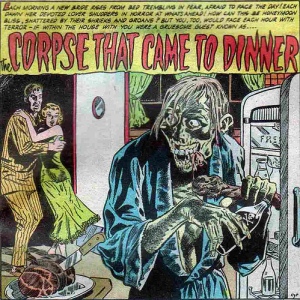

It’s gratifying to find a few of my all-time favorite stories and artists here (like Basil Wolverton‘s “Swamp Monster” from Weird Mysteries #5, June 1953, pictured above, left; and Reed Crandall‘s “The Corpse That Came to Dinner” from Out of the Shadows #9, July 1953, above, right). It’s even more gratifying to find so many surprises and—in the fresh context of Four Color Fear—stories I’d long ago read and shrugged off so revitalized by what Sadowski places them between and/or alongside here.

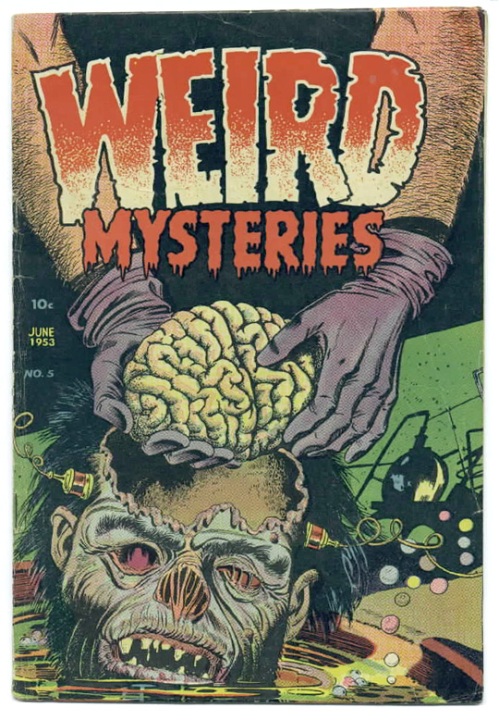

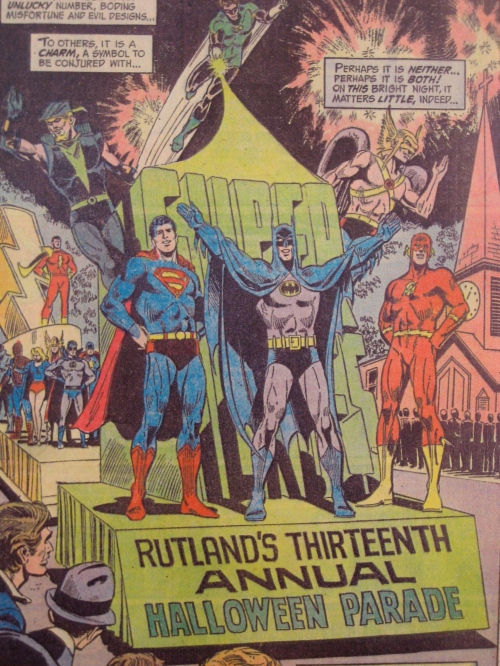

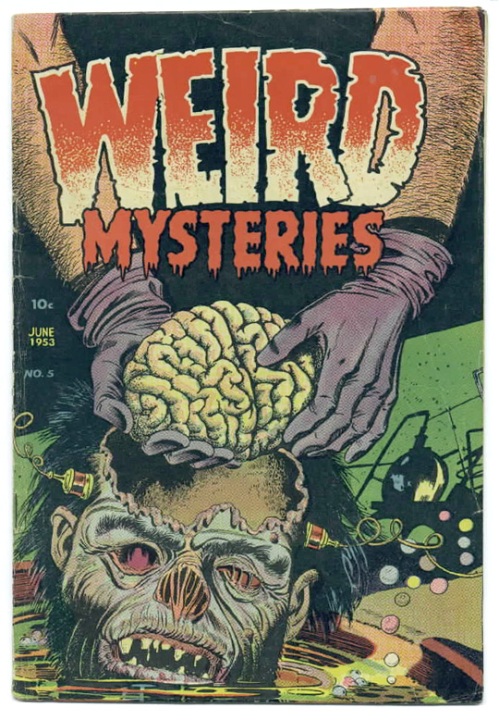

[A notorious Bernard Bailey cover for Weird Mysteries #5 (June 1953) that I’ve always included in my own lectures on the Pre-Code horror comics, and that is featured in both Four Color Fear and The Horror! The Horror!; a small taste of how extreme the Pre-Code horrors could be and often were.]

___

Caveats: Aside from quibbling with some of Sadowski’s selections, which I won’t do here (see “addendum & full disclosure” note at the end of this post; I have plenty of my own personal favorite Pre-Code horrors, and if anyone’s interested, I’d be happy to talk to an agent, editor, or published about putting together such a volume), a fuller working knowledge of the horror genre in all media would have lent even more weight and insight to this collection. While it may seem like hair-splitting to criticize such an incredibly generous tome, genre studies and horror genre academia in particular has been thriving, and the ways in which Pre-Code horror comics in particular both “borrowed” (often blatantly ripped-off) from all that came before, and anticipated much of what was to follow, is an aspect of the genre’s evolution in all media that has been lazily cited for decades but rarely, almost never, really brought to light. This was a stellar opportunity to do so, but Sadowsky and Benson keep their focus on the context of comic book history alone, which is occasionally a frustration for this reader.

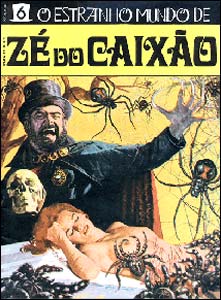

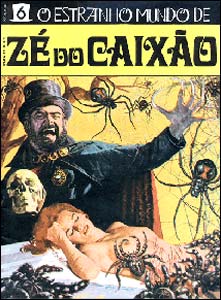

The ways in which particular comics stories appearing here stole from their precursors—in gothic, pulp, and radio genre fiction, as well as popular writers of their era—is mentioned, but rarely specifically cited. In other cases, a knowledge of past and future genre landmarks would have lent some heft to the legacy under scrutiny: for instance, a sample of how Matt Fox‘s Pre-Code comics covers reworked his venerable Weird Tales pulp covers would have been welcome. Mentioning the uncanny parallel between the Iger Studio “Experiment in Terror” (from Haunted Thrills #13, January 1954) and the final episode (“Theory”) in José Mojica Marins‘s notorious horror portmanteau film O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão/Strange World of Coffin Joe /The Strange World of Ze do Caixao (1968) would have added resonance to the whole (in fact, Marins’s “Theory” is almost identical to “Experiment in Terror” in many particulars, right down to the philosophical intent of the madman staging the grueling ordeal; that Marins also spawned his own Brazilian horror comics only intensifies the associative links begging to be drawn here). Instead, we’re treated to another Jerry Iger anecdote that has nothing to do with the story itself (though it’s neat to see the connection made—in a caption—between the story and its apparently intended cover art, which instead was published eight months later on another title, Fantastic Fears #9).

The ways in which particular comics stories appearing here stole from their precursors—in gothic, pulp, and radio genre fiction, as well as popular writers of their era—is mentioned, but rarely specifically cited. In other cases, a knowledge of past and future genre landmarks would have lent some heft to the legacy under scrutiny: for instance, a sample of how Matt Fox‘s Pre-Code comics covers reworked his venerable Weird Tales pulp covers would have been welcome. Mentioning the uncanny parallel between the Iger Studio “Experiment in Terror” (from Haunted Thrills #13, January 1954) and the final episode (“Theory”) in José Mojica Marins‘s notorious horror portmanteau film O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão/Strange World of Coffin Joe /The Strange World of Ze do Caixao (1968) would have added resonance to the whole (in fact, Marins’s “Theory” is almost identical to “Experiment in Terror” in many particulars, right down to the philosophical intent of the madman staging the grueling ordeal; that Marins also spawned his own Brazilian horror comics only intensifies the associative links begging to be drawn here). Instead, we’re treated to another Jerry Iger anecdote that has nothing to do with the story itself (though it’s neat to see the connection made—in a caption—between the story and its apparently intended cover art, which instead was published eight months later on another title, Fantastic Fears #9).

Sadly, it must be noted that the cover is the book’s greatest liability. Any one of the actual Pre-Code covers in the gallery would have done a better job of properly promoting and packaging the contents. I see what the designer was trying to do (conceptually a clever fusion of images from the Reed Crandall splash for “The Corpse That Came to Dinner” and page 4 of Howard Nostrand’s art for “I, Vampire,” from Chamber of Chills #24, July 1954, reprinted on pp. 209-213), but graphically it’s a failure and easily lost on both the book store shelves and online venues. The book’s title is lost, too, and the addition of a fancy varnish-printed blood splatter design (front and back) only further complicates the design. Again, I get the intention and concept, but… sigh. As with the otherwise definitive Fantagraphics Book on the late, great underground (horror) cartoonist Greg Irons, You Call This Art?!!: A Greg Irons Retrospective by Patrick Rosenkranz (2006), what should have been an easy-sell given the incredible imagery associated with the chosen subject has been compromised by a cover that simply confuses and/or repels the eye (and not in the way horror comics intend to repel). Here’s hoping either future editions or future collections from Fantagraphics better serve the genre and their own product.

In all other departments, this is a terrific book, and highly recommended.

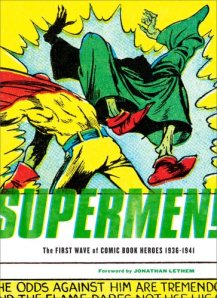

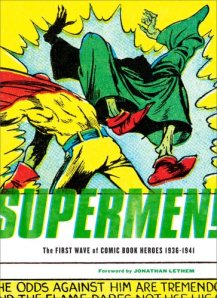

This is a marvelous companion to Sadowski’s earlier Fantagraphics collection Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941 (2009), in which Sadowski similarly shed light on too-long-forgotten gems, curios, and entertainments from comics creators and publishers that have been essentially ignored and/or disposed of by the forces that shape comics history. As in Supermen!, Sadowski’s appetites and reach prove satisfyingly diverse, all-encompassing, and yet quite selective— without catering to traditional, constrictive standards of “taste.” Sadowski knows that some of the most outrageous, insane, and appalling vintage comics stories and imagery are also among the most fascinating; and nowhere is this truer than in the horror comics of the Pre-Code boom years. Four Color Fear also whets this reader’s appetite further for Sadowski’s forthcoming Setting the Standard: Alex Toth (announced for spring 2011 publication).

This is a marvelous companion to Sadowski’s earlier Fantagraphics collection Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941 (2009), in which Sadowski similarly shed light on too-long-forgotten gems, curios, and entertainments from comics creators and publishers that have been essentially ignored and/or disposed of by the forces that shape comics history. As in Supermen!, Sadowski’s appetites and reach prove satisfyingly diverse, all-encompassing, and yet quite selective— without catering to traditional, constrictive standards of “taste.” Sadowski knows that some of the most outrageous, insane, and appalling vintage comics stories and imagery are also among the most fascinating; and nowhere is this truer than in the horror comics of the Pre-Code boom years. Four Color Fear also whets this reader’s appetite further for Sadowski’s forthcoming Setting the Standard: Alex Toth (announced for spring 2011 publication).

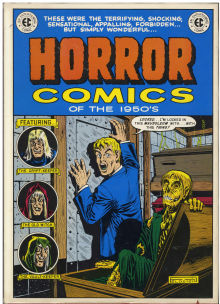

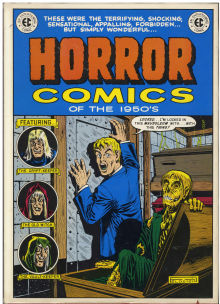

While much work that was hacked out by impoverished creators working for opportunistic packagers and publishers paying chicken scratch rates has justifiably been neglected, both Sadowski and Benson make a strong case for preserving and reprinting the cream of such publishing backwash, and Four Color Fears is a welcome remedy and companion to the handsome EC Comics reprint volumes (many of which Benson contributed to or packaged himself) that have been available since Nostalgia Press‘s historic Horror Comics of the 1950s (1971, edited by Ron Barlow and Bhob Stewart) enshrined EC Comics as the peak product of the Pre-Code horror publishers. Ever since, EC’s horror comics have almost exclusively dominated any published reprint editions of the genre’s fertile Pre-Code explosion.

While much work that was hacked out by impoverished creators working for opportunistic packagers and publishers paying chicken scratch rates has justifiably been neglected, both Sadowski and Benson make a strong case for preserving and reprinting the cream of such publishing backwash, and Four Color Fears is a welcome remedy and companion to the handsome EC Comics reprint volumes (many of which Benson contributed to or packaged himself) that have been available since Nostalgia Press‘s historic Horror Comics of the 1950s (1971, edited by Ron Barlow and Bhob Stewart) enshrined EC Comics as the peak product of the Pre-Code horror publishers. Ever since, EC’s horror comics have almost exclusively dominated any published reprint editions of the genre’s fertile Pre-Code explosion.

Given the high quality of the EC line, that’s been completely understandable, but now that the entire EC line has been repeatedly (and beautifully) reprinted, republished, repackaged, and immortalized ad infinitum, it’s high time the other Horror Comics of the 1950s were allowed to rise from the dead.

That classic 1971 book was a beautiful start; four decades later, Sadowski and Benson have at last graced us with a worthy followup.

– S.R. Bissette, Mountains of Madness, VT

__________________

Addendum & full disclosure: Having been one of the active creative collaborators (I was the penciler) on DC Comics’s Saga of the Swamp Thing when that title was rejected by the Comics Code Authority (with SOTST #29, cover dated October 1984)—which was the wellspring for the entire Vertigo Comics line—I’ve had first-hand experience with (a) the Comics Code’s policies and (b) horror comics bucking the CCA. FYI, we did not change anything in the issue; it was sold without the CCA Seal; sales went up; after two more issues, we no longer had to submit to the restrictions of the CCA. Though I repeatedly asked for a copy of the extant CCA Code itself during that (brief) debacle, none was provided, and it seemed despite the fact that DC honcho (and my former Kubert School instructor) Dick Giordano was DC’s rep on the CCA, nobody at DC Comics actually had a copy of the then-extant CCA Code to send me.

Finding this perverse process fascinating, and loving horror comics anyway, I spent much of the next five years researching and collecting Pre-Code horror comics. The fruits of that research and collection became my traveling slide lecture “Journeys Into Fear,” which I debuted as a one-hour talk at Necon (an annual July gathering of horror writers that I attended faithfully from the late 1980s until 1999, and which I sorely miss being part of) in the summer of 1988 or ’89. I expanded the lecture into a two-hour-plus illustrated presentation that was eventually presented in over 60 venues throughout the 1990s in the U.S. and abroad, often as fund-raising events for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Along with presenting the lecture (at my own expense) as a CBLDF fundraiser during the mid-1990s Spirit of Independence tours, these venues included the Copenhagen Comic Art Library in Copenhagen, Denmark; The University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut; Utica College, Utica, New York; Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the 2nd and 3rd Annual World Horror Conventions; the San Diego Comics Convention; Marlboro College, Marlboro, VT; Bennington College, Bennington, VT; Henderson State University, Arkadelphia, Arkansas; FantAsia Film Festival, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; and many others. In 1999, “Journeys Into Fear” was expanded into a one-week seminar for Smith College in Northampton, MA. Though I pitched Journeys Into Fear as a book proposal numerous times over the decade, there was no interest from publishers.

I’m glad the times have changed!

-SRB

Cartoonist librarians, Jen Vaughn and Caitlin McGurk.

Cartoonist librarians, Jen Vaughn and Caitlin McGurk.